Project Update: 📗 Design Diary 4 – Players and Powers

Matt here for Design Diary number 4! Today, I'll be sharing more about how we decided who the players would represent and how we untangled and presented all the many different types of actions you can take to take on the climate crisis.

In our previous journal entries we described our goals, the antagonists of the game, and the resources in play. In this entry, we look at who the players represent in the game and what they can do about the problems at hand with the resources that they have.

In our previous journal entries we described our goals, the antagonists of the game, and the resources in play. In this entry, we look at who the players represent in the game and what they can do about the problems at hand with the resources that they have.

Who Should the Players Represent?

We agreed the game should have a global scale so it made sense to first explore the idea of each player taking on the role of a government. Each player would be in charge of a country, or group of countries (in a realistic or imaginary world, we weren’t sure at the time), using political will and financial capital to roll out policies and technologies from an opportunities deck.

Players would have individual agency over their economies but their emissions would be added to a common pool (the atmosphere), which would tie everyone to the same global engine of doom and create a strong incentive for players to cooperate.

Given the practical requirement of a 1–4 player game, we needed to work out a list of world powers for the players to represent. But splitting the world into four is not simple! We wanted to include as much of it as was reasonable, giving players meaningful options and agency without reproducing the Western idea that only wealthy “developed” countries had a role to play.

Our list was heavily influenced by the book The 100% Solution which outlines four major players in the struggle as the United States, China, Europe (plus other “developed” countries), and India (plus other “developing” countries). We wanted the Global South – not a country, but a block of countries with broadly similar trajectories – to have a seat at the table. Those are the countries that are the least responsible for the climate crisis yet are the most affected by its consequences. So we expanded India to include all of the Global South and then renamed it to the Majority World, which better reflects its scale and highlights that it represents most of humanity.

We didn’t want to perpetuate the myth of a level playing field sustained by many games, so we imagined that the players would have asymmetrical starting values and abilities. We also figured this would add variety and texture to the game and potentially give each player a kind of role to play – similar to the roles in Pandemic.

What Can the Players Do About the Problem?

We began with the premise that there would be a collection of standard actions that the players could do along with special actions that would be printed on policy and technology cards. Players could put these cards into play by spending two currencies: financial capital and political power.

In the very first iteration of the game, this menu of standard actions was pretty simple:

- Add energy capacity

- Buy and sell energy

- Exchange ideas

Players could produce energy, sell it to the other players, and hand their cards to each other.

By version 1.17, this list had blossomed into a much bigger menu:

- Buy Dirty Energy Plant

- Buy Clean Energy Plant

- Decommission Dirty Energy Plant

- Give Foreign Aid

- Share Opportunities

- Buy or Sell Energy

- Reforestation

- Sequester Carbon

This was a pretty heterogeneous list. And since some of these actions took place during different steps during the order of play or adjusted certain values, the player aid began to look pretty complicated.

This was functional but a bit awkward and certainly not something you’d describe as elegant or easy. The complexity of this system and all of the resource manipulations that were required meant for a much longer play time than we wanted.

In February of 2021, we embarked on an experiment to simplify the game by entirely removing its two main currencies: financial capital and political power. We moved to an economy that used cards as currency instead. Players spent opportunity cards, and as a result, each action now had an “opportunity cost.” In a sense, this was like turning Terraforming Mars into Race for the Galaxy.

Standard Actions Become Starting Projects

Around this time, we also decided to move all the standard actions of the game onto a set of starting project cards for each player. In doing so, we were able to eliminate the menu of standard actions altogether. If an action wasn’t on a card in your tableau, you now simply couldn’t do it. These starting project cards were also the perfect surface for differentiating the players. All we needed to do was give each player a different set of starting cards.

Here’s an evolution of the starting cards for the U.S. player:

Fostering Communication and Cooperation

In our early prototypes, cooperation was limited to swapping cards and buying and selling energy. Once we started to lean into our new design that featured a starting tableau of differentiated player powers, we found lots of new opportunities for players to assist each other, right from the start of the game:

- The U.S. is good at R&D and can discard cards to go “fishing” for solutions that might benefit another player. They can then pass that card to the other player using their Climate Debt Repayments card.

- China starts out with the ability to export clean energy technology which can help other players meet their electricity demand.

- Europe can help by giving other players resilience tokens and can help pull the other players’ communities out of crisis.

- The Majority World can forecast upcoming crises that often affect every player.

We did notice one issue crop up repeatedly in playtesting: once players received their initial hand of cards, they suddenly got tunnel-vision – it was difficult for players to propose ideas to the group since players tended to get hyper-focused on their own hands, tableaus, and player boards. This came up in several post-game debriefs: players expressed frustration with an inability to make proposals to the group. It was like the opposite of the “alpha player'' problem. Players had so much autonomy that they found it difficult to talk about the big picture.

We solved this by creating the Conference step. In this new step, players could forecast upcoming crisis cards, debate global project cards, and generally talk strategy together. Crucially, this step occurred before any player had their new hand of playing cards. This gave everyone some time to focus on the bigger picture together. Thematically, it resonated: it gave the feeling of the world coming together at a COP conference where they could make plans and promises that they could try to fulfill but (since they didn’t yet have their hand of cards) couldn’t do with 100% confidence.

Making the Players Feel Powerful

Once we changed our currency system, we identified another benefit. In the old design, cards were typically purchased and their effect was recorded on the player board – and then the card was largely forgotten. In our new design, cards could be put into play for free but players would need to pay a cost in order to activate the action on them. This meant that we could design recurring actions.

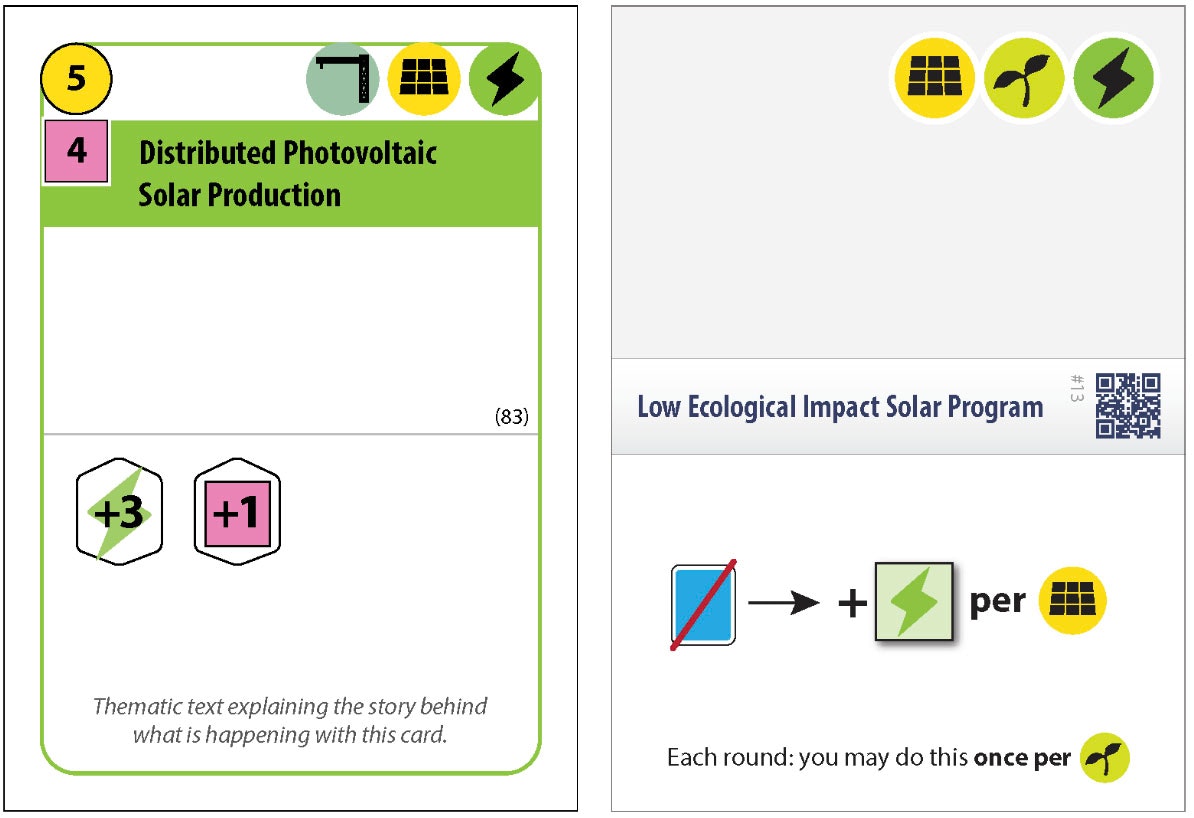

This, in turn, led to experiments where we tinkered with different ways the cards could scale using the tags printed on them. Prior to this, the tags were more like passive categories – sometimes they mattered, but that was the exception, not the rule. With the new card design, we could let players put a new card into play quickly (but fairly inefficiently) and then let them really scale it up into something far more powerful. Here’s a comparison:

The card on the left is from an early prototype. It cost 5 financial capital and 4 political power. When it was played, the player would increase their clean energy production by 3 and their political power income by 1 each round. The card was then put in a loose tableau of cards that the player had rolled out, where it could essentially be forgotten.

The card on the right is from the final prototype. It can be played for free on top of any stack. Once played, the action on it can be used if a player discards a card from their hand. This will gain 1 clean energy plant for each solar tag in that card’s stack. Since the card already has a solar tag, the player can discard 1 card and gain 1 clean electricity plant right away.

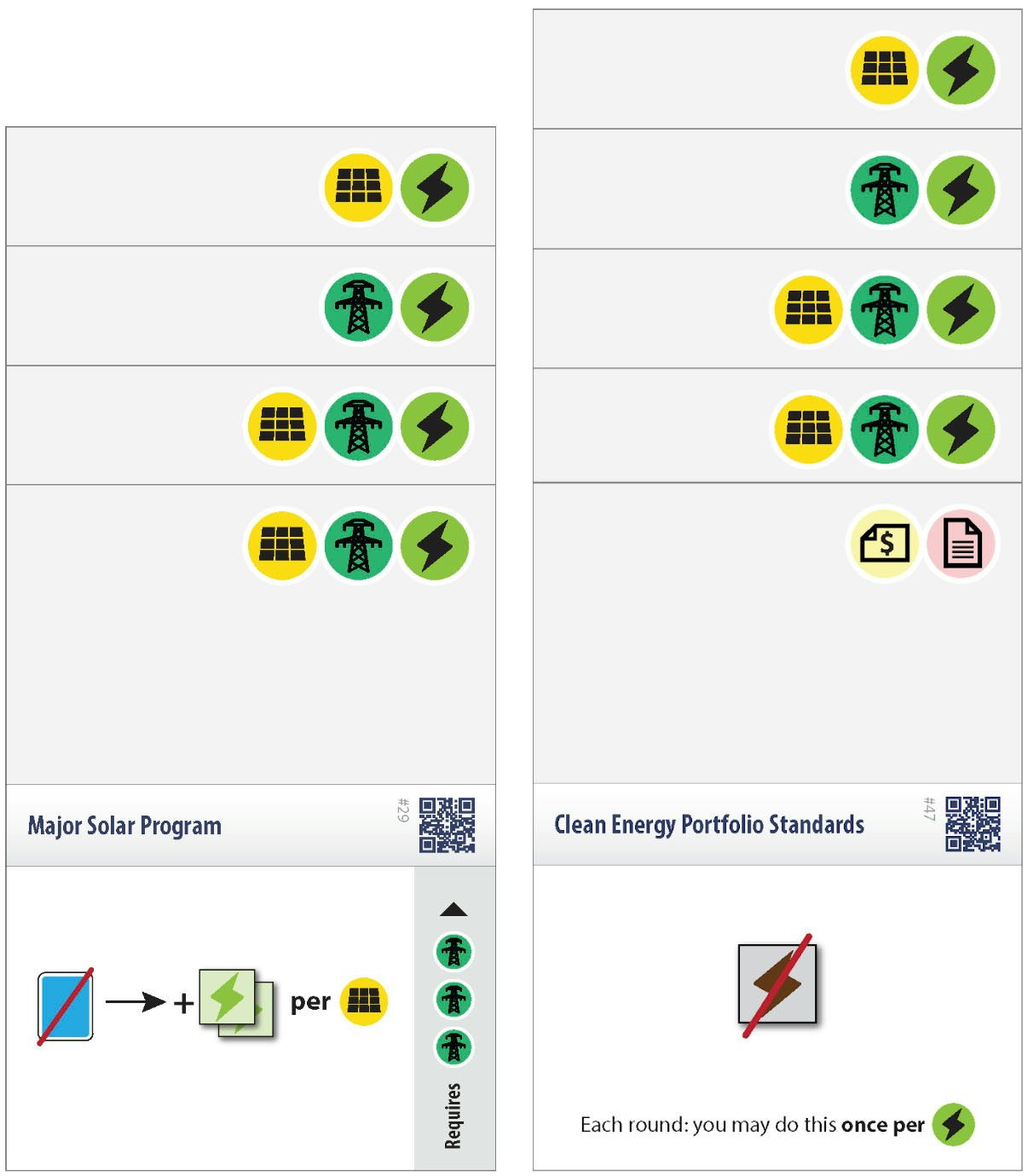

On the left is a more extreme example. Here the player can gain 2 clean electricity plants for every solar tag in this card’s stack for each card they spend. In this example that’s 6 plants per card! And the only limit to the number of times a player can do this is the number of cards they have to spend.

We also let players play cards on top of existing stacks. The example on the right shows what would happen if a player placed a “Clean Energy Portfolio Standards” card on top of their “Major Solar Program.” This card lets the player remove 1 dirty energy plant for each clean electricity tag in the card’s stack each round. In this case, 4 dirty plants, for free, each round.

This ability to add cards on top of other cards led to an understanding that your new solutions could be built on the foundations of your older solutions and also conveyed an exciting feeling of momentum.

A Diversity of Solutions and Tradeoffs

As we worked through the design of these cards, we wanted the game to make it clear there is no single solution to the climate crisis – that many different solutions, all working together at the same time would be required.

More than Just Decarbonization

We wanted to get across a key lesson from our research – that many climate solutions aren’t just tied to decarbonization and energy. While we decarbonize the world, it’s equally vital to build resilient communities, restore ecosystems, improve infrastructure and bolster international cooperation. For instance, expanding access to healthcare means vulnerable people will be more protected from the impacts of climate change (think heatwaves, fires, storms, as well as food shortages and epidemics).

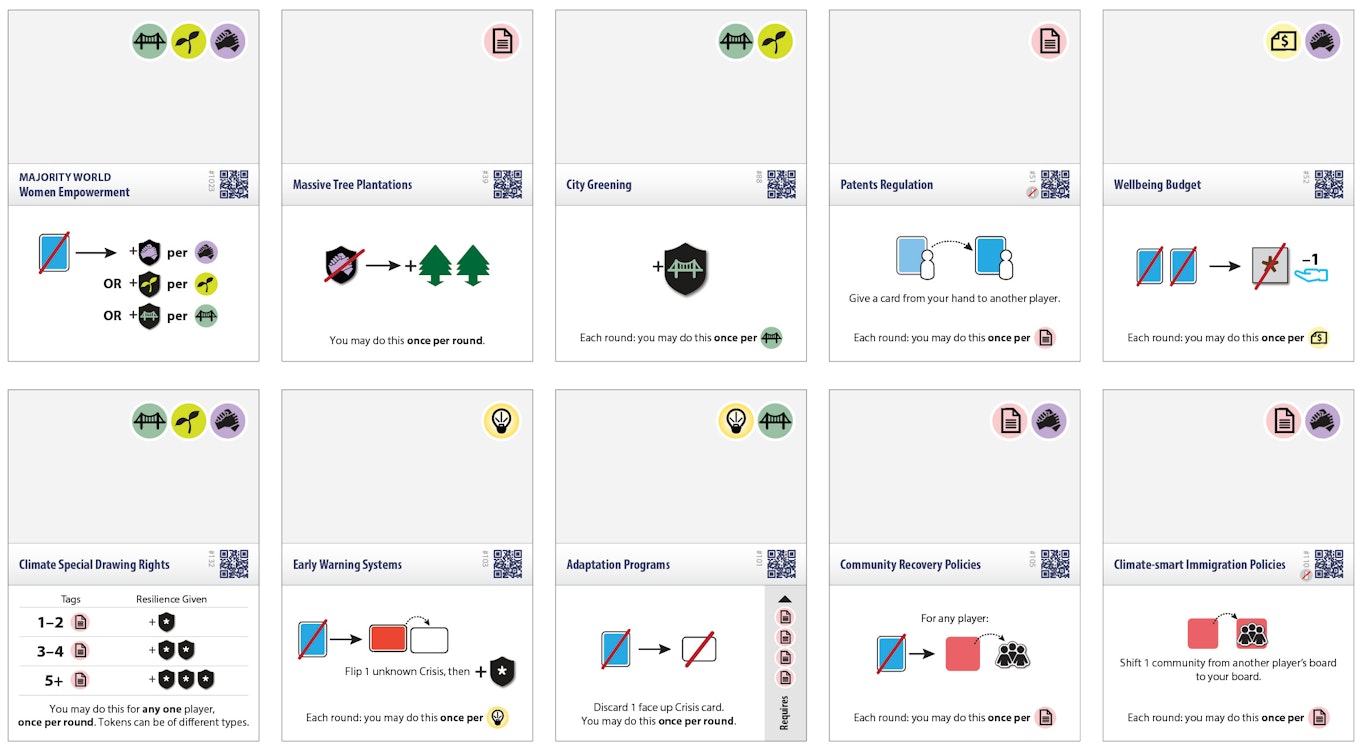

Here’s a small sampling of cards that look beyond decarbonization and energy:

- Women’s Empowerment, Rewilding, City Greening, Regenerative Agriculture, Universal Access to Healthcare, and many more that build resilience.

- Environmental Movement, Social Movement, and Community Wealth Building projects as well as various climate finance projects that increase opportunities to roll out future solutions.

- Community Recovery Policies and Climate-smart Immigration Policies that pull communities out of crisis and care for them.

- Indigenous Peoples’ Forest Tenure, Mangrove Restoration, and Peatland Protection and Rewetting that increase land-based sequestration.

- Foreign Aid, Climate Debt Reparations, and Patents Regulation that help players share opportunities with each other.

- Adaptation Programs and Early Warning Systems to help predict and mitigate upcoming crises.

All told, we came up with over 130 different opportunity cards and two dozen starting projects!

Tradeoffs

But these solutions couldn’t all be equally valid at any given time. We also wanted the players to make difficult tradeoffs! Through many rounds of playtesting, we were able to hone these and worked to increase their importance in the game through the design of the actions on the opportunity cards. Some key tradeoffs included:

- Perfect the enemy of the good? Should you design high efficiency projects that will take longer to mature, or do as much early action as you can – even if it’s less efficient?

- Mitigation or adaptation? Should you focus on mitigation (reducing greenhouse gasses emissions) or adaptation (build resilience)? Both are needed; what’s the right balance?

- At home or abroad? When should you help another player achieve their goals or protect their communities when it would mean less investment in your own economy?

- How much risk is right? Do you invest only in technology, hoping the crises this round will be mild and spare your communities? Do you start a project which requires a lot of future investment that you may not be able to afford? Will this geo-engineering project work? Should you invest in R&D even if it might not pay off this round?

We noticed that we started to read climate news articles with the dynamics of the game front of mind. Just about anything, it seemed, could be turned into an opportunity card (or a planetary effect or a crisis card). By the time we finished, we had a huge suite of opportunity, global project, and crisis cards on our hands.

Managing Complexity

The new play patterns and the diversity of options made the players feel far more powerful and creative. Over the course of development, we found that the problem space needed to be bounded, however, to prevent players' “heads from exploding.” (We have footage of several people using this exact phrase before we solved this problem.)

Natural Restrictions and Simplifications

We found some helpful and natural restrictions and simplifications helped bound the problems into a more human-manageable size:

- We introduced a limit to the number of stacks of cards that a player could manage (at first 4, then 5) and ruled that only the topmost card in each stack was available. When we started, all of the cards in each player’s tableau were spread out in a large pile and the player might need to evaluate every one. We also tried limiting each stack’s depth but found that this was unnecessary.

- We didn’t allow players to move cards around in their tableaus. Doing so would have meant players would have to re-evaluate every card and its position. Far too time consuming!

- We severely limited the players ability to exchange cards, making it a special action they had to unlock in order to use. This felt wrong to me, initially: I figured this would be an essential component of cooperation. Initially we let players hand cards to each other at the cost of 1 political power. Then we let players simply swap cards whenever they wanted. But this often meant that players would attempt to internalize the entirety of each others’ tableaus in order to best min/max the potential of each card. This obviously led to much longer play time and a tendency for some players to attempt to direct the action (the “alpha player” syndrome). When we added the card passing restrictions, these problems disappeared, play time became much more manageable, and there was still plenty of cooperation.

- We reduced the number of ways you could play a card. We experimented with cards that had “instant effects” (that were played and then discarded) and cards with rollout costs that you’d have to pay in order to add the card to your play area. We removed all of these exceptions in favor of a single, easier-to-understand system.

- We moved global project cards out of the opportunity deck. The global project cards used to be mixed in with all of the opportunity cards. Players would draw them into their hands and then have to try to make a case to the group for rolling them out – while everyone was focused on improving their local economy. We pulled these out of the opportunity deck and into their own deck when we introduced the Conference step.

Abandoned Ideas

We also tossed a number of ideas from the game to reduce complexity and better model what was going on. Here are some of the many ideas that got the ax:

- An elaborate model of battery technology which attempted to model how intermittency could be mitigated. We scrapped this after discussions with Justin Vickers for a much simpler system that also made for a better model.

- Clean energy storage. Turns out, you can’t store electricity (at least in these quantities) for 4–5 years anyway.

- Buying and selling energy. Early versions of the game allowed players to buy and sell dirty energy (and with some technology cards) clean electricity with each other.

- Financial capital and political power. These currencies bogged the game down and were presented with a level of fidelity that was largely just made up. We replaced them with a system that used opportunity cards as currency instead.

- Dirty energy demand. This represented the fact that legacy systems that run on fossil fuels can’t run on electricity. We ditched the idea of “reducing dirty energy demand” in favor of representing these sources of emissions directly with different tokens. We were then able to model electrification by removing these tokens in exchange for increasing electricity demand.

- Innovation checks. In earlier versions, many of the cards that used speculative technologies had a system where you’d pay for the card and then draw further cards to see if you were successful, using a system similar to 7th Continent. We simplified this system considerably and limited it to only the R&D cards.

A Long Evolution

Here’s a visualization of how some of the starting actions evolved over the course of Daybreak’s development.

In the next post, we’ll look at how we designed the winning and losing conditions for the game.

Comments

7